Buying & Selling

💭 Project Description

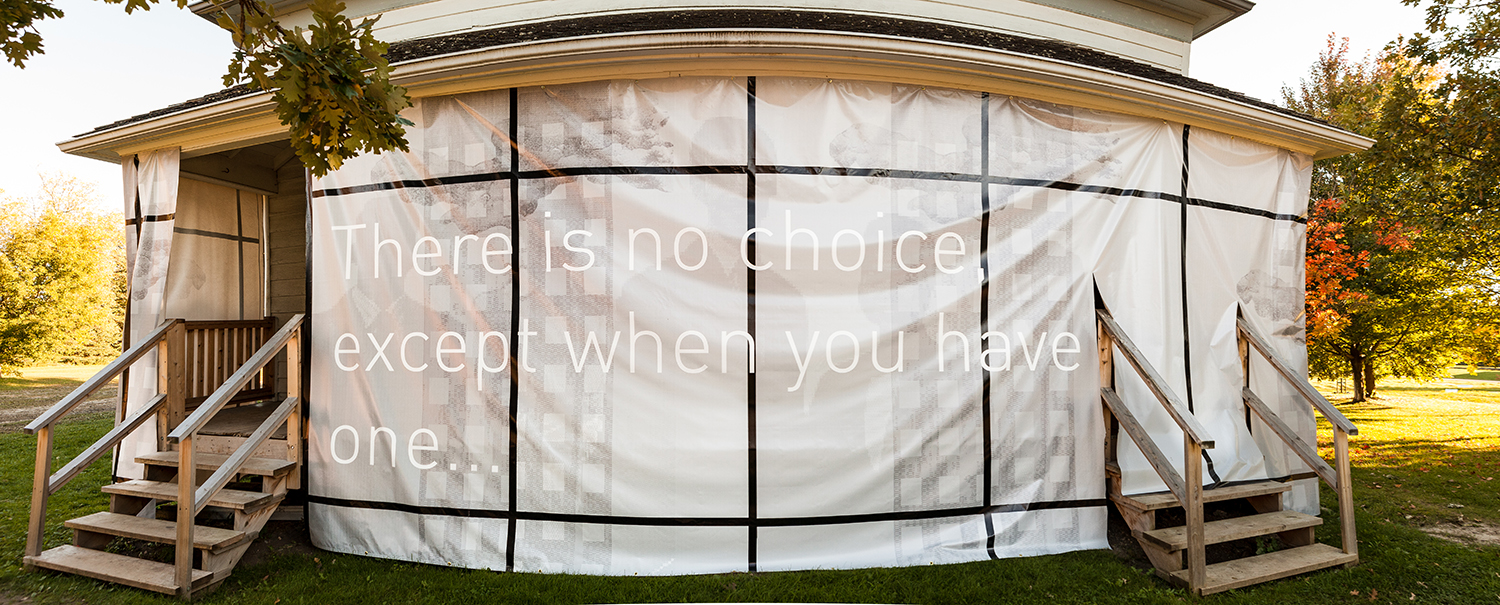

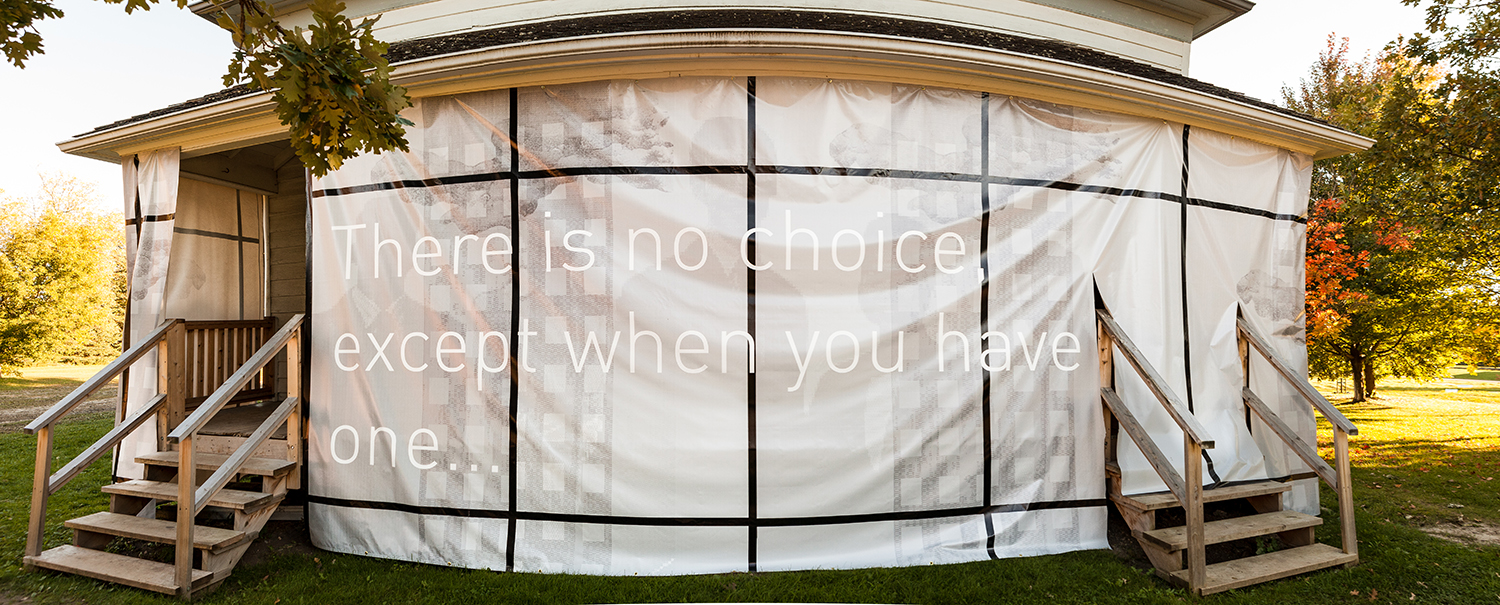

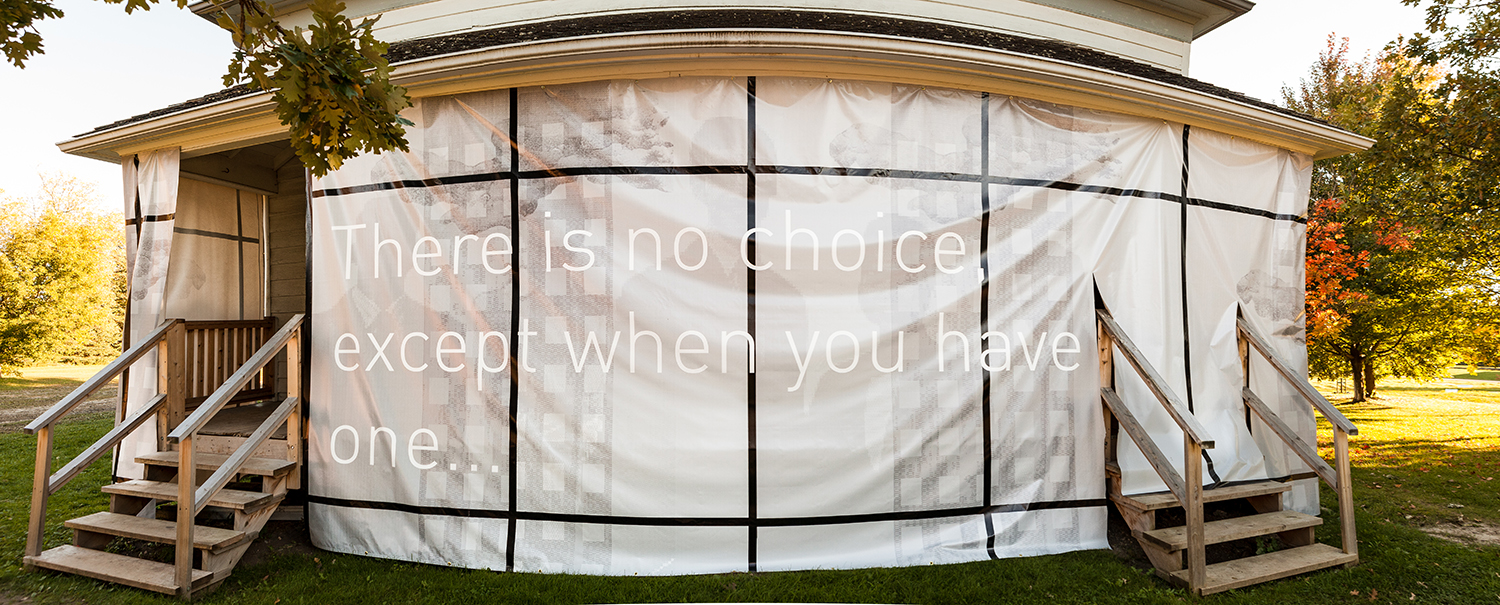

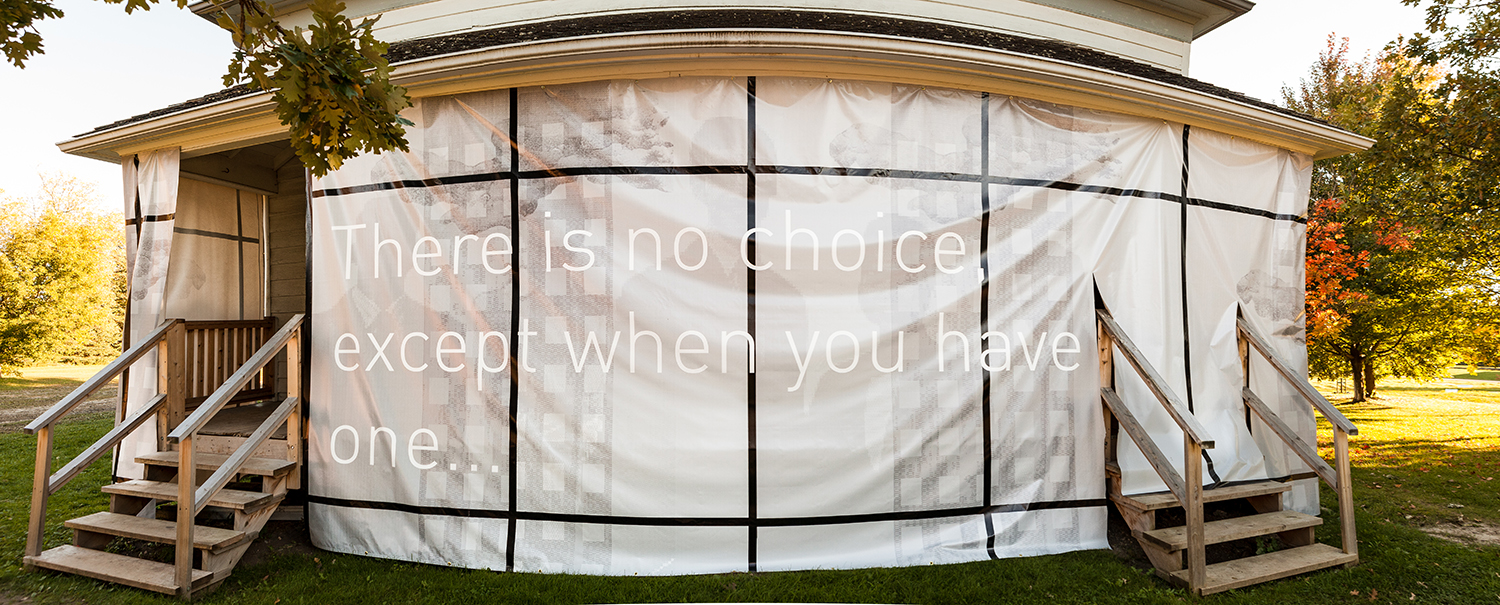

Commissioned by 7 Continents to create an exhibition for Land|Slide at Markham museum, DoUC worked in partnership with Sara French to explore the current state of local and global housing options. With relatively limited choice in how we acquire a place to live and what type of housing we have available to us, DoUC wanted to know, how do we create more choice and how can those choices manifest in Markham, Ontario?

Before considering the specific housing options currently available to residents of Markham, and more broadly Canada, DoUC began by examining the concept of choice in broad terms. What does it mean to have a choice and how do people determine the best choice in a given situation? What choices made in the past have influenced and resulted in the way we currently live?

Commonality of basic needs is what unites us as humans. However, how we meet those needs—as well as our wants—is what often separates us. In researching current housing options locally, there was a peripheral goal of examining who the market is truly accessible to and if the available choices are created for the people in need of shelter or merely to maximize the financial gain of developers. Of specific interest was looking at housing choice through the lens of immigration, trying to understand why housing typologies from around the globe have not also made their way to Canada following the patterns of immigration across the country.

This is what led to the idea of designing the exhibit to be an immersive experience for visitors, proposing new choices in housing based on global profiles and housing typologies. The experience was facilitated by a community outreach officer from 7 continents, Reena Smith. Reena acted as a guide for Markham’s ‘potential buyers’, leading people through the experience to learn about the options available and helping them to choose and close on the most appealing and appropriate option that met their needs and fulfill their wants.

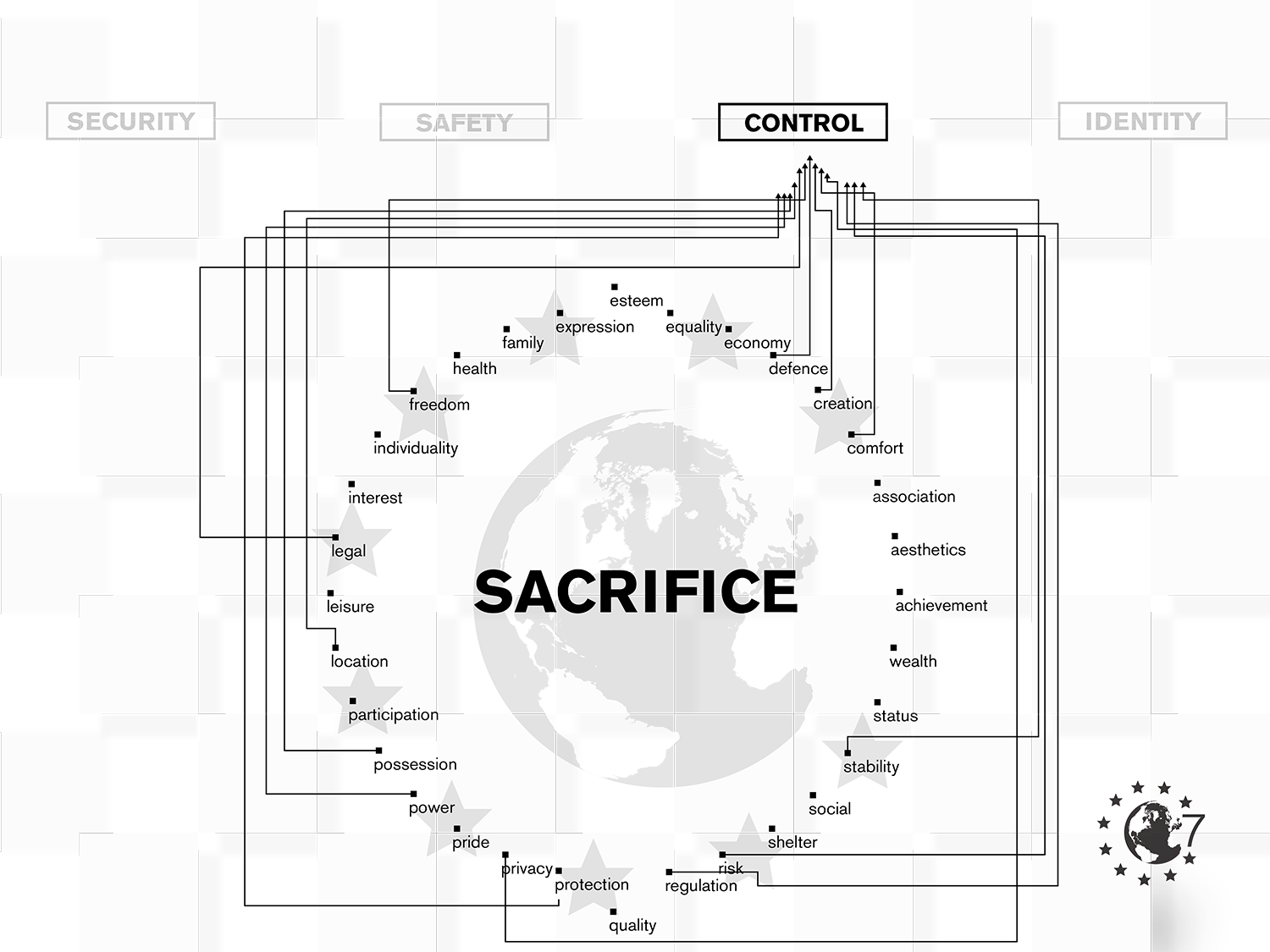

Following the Markham exhibition, a synopsis of Buying & Selling was presented at the Hong Kong Shenzhen Biennale, including a video message from Reena Smith discussing growth in Markham and the potential for global typologies to play an influential role in the future of housing. A slightly different take on the examination of how people make choices to fulfil the requirement of shelter was considered for an installation created for the works art and design festival in Edmonton that further explored what sacrifices one makes to attain security, safety, control and identity through shelter.

The project team included: Aliya Tejnai, Christopher Pandolfi, Natasha Basacchi, Sara French, and Simon Rabyniuk.

DoUC is interested in pursuing further research and projects that build on the ideas from Buying & Selling.

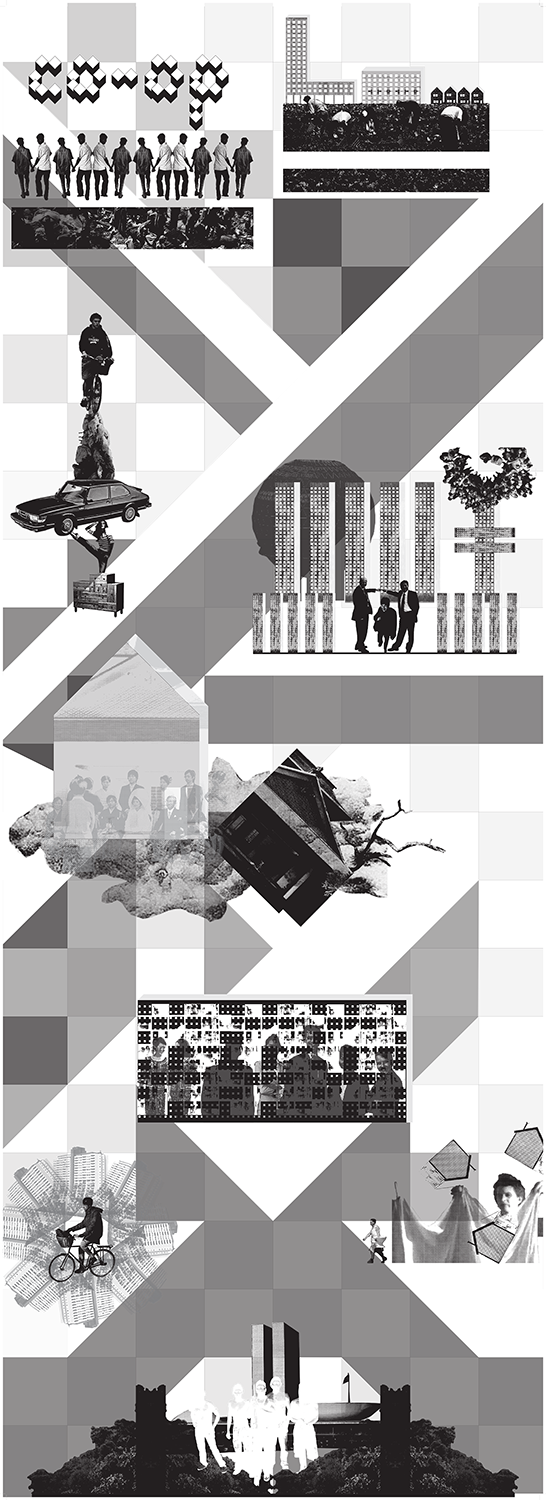

Buying & Selling poster showcased at the Hong Kong Shenzen Biennale, 2013

To commemorate DoUC’s 10 year anniversary, we have organized an interview series highlighting past DoUC projects.

We wanted to take this milestone opportunity to revisit projects in a fun and reflective way, calling on the perspectives of both past and present DoUC team members. Shifting from objective and brief project descriptions, we revisited our work with a renewed intimacy. With more personality. We hope this series provides deeper insight and understanding to past projects. Or, is simply a fun read!

To help you navigate this series, we recommend first reading the project description for context. Then, you can explore the interview dialogue. Enjoy! 🙃

ℹ️ Buying & Selling interview was conducted with Chris Pandolfi (CP), Natasha Basacchi (NB), and Simon Rabyniuk (SR).

In your own understanding, what was this project attempting to address?

NB ⤳ An exploration of the basic housing needs and vernacular design in major cities around the world. The exhibit was a performance on presenting these options to the city of Markham to show an alternate to our North American suburban solutions.

CP ⤳ Buying & Selling was a way for DoUC to engage the public around the idea of choice and how we make choices in the housing market with a particular focus on the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH). We wanted to create a space where people could explore their feelings and how and why they make choices in the housing market. One of the motifs we played with was this idea “do you actually have a choice” or is it that we all are just managing with the dysfunctional relationship between the market economy and planning system that was there to protect the interest of private property. The project seems more relevant now with everything that is going on across the GGH.

SR ⤳ Bidding war, bully bid, house poor, hot market, over housed, empty bedrooms, character of the neighbourhood, exit strategy, rock-bottom interest rates, the exclusive network, lender of last resort, offer with no conditions, renoviction. The everyday language of Canada’s real estate industry was the subject of Buying & Selling. Said differently, Buying & Selling addressed the idea of a Canadian housing cultural imaginary.

An imaginary can describe either a society’s or an individual’s belief structure. Cultural imaginaries describe commonalities held between people, like shared aspirations, or ideas about what is natural and given. In the context of housing, the common aspiration and the ‘natural’ pursuit is housing ownership—to buy, of course. x.x Said differently, cultural imaginaries define the limits of what people consciously, or unconsciously think is possible. This aspect of cultural imaginaries, as an edge or boundary for what people believe is natural or possible in housing in Canada, is what was so interesting for me about the project.

Diagram exploring people’s behaviours and attitudes in the housing market.

In the project description found on the studio’s site, it states that the team examined the concept of “choice” in broad terms—specifically what does it mean to have a choice and how do people determine the best choice in a given situation. You found that common basic needs are what unites us as humans, but how we meet those needs and wants is what often separates us. How did those separations manifest in your findings when it comes to choices being made for buying/selling housing? Why do you think they were this way?

CP ⤳ Two of our biggest components of the work was first trying to show different housing policy and typological formats from around the world. We tried to show examples from the different continents and gave priority in showcasing examples from the continents with the most people. We wanted to show how other places around the world considered housing their populations and how their local culture played a role in the design of the typologies and also when they did not. We also wanted to showcase how these different places created policy and the values that drove those policies so people could reflect on how we as a society in Canada were doing that or not doing that as well.

The second part, which was also interconnected to the entire project, was for us to make up an entirely fictional organization called 7 Continents. 7 Continents was a bit of a shady global community organization that was interested in housing the world’s population. The design of the pavilion was based on the org and Sara French, our friend and wonderful performance artist, played the community outreach officer that would guide people around the pavilion and the drawings and different interactions.

In terms of the basic needs and as humans we used Manfred Max-Neef’s framework for fundamental human needs and used different elements from our research, like interviews and stories to help us better understand how people made choices in context. However this was by no means exact and was purely helping us further the exploration.

Can you tell us a bit about your process behind the final execution. Did you find anything surprising? How did that affect your process/solution?

CP ⤳ The process to create this project was very enjoyable because it was very experimental. We let our research drive our work and our message and most of all our format. I don’t think we knew at the start of the project exactly what we wanted to do…we just knew we had some basic questions that we wanted to explore and let these simple questions like why do we live the way we do? And why is the housing market like this? guide the project…poof interactive performance installation that engages people on housing choices.

Were there any obstacles, challenges, or difficulties that you experienced while researching or building the solution? How did you navigate them?

CP ⤳ There are always obstacles when you are doing a global research project. Language barrier being a main one. By not being able to understand or read different languages you are always skewed with english based resources that may not give you a full picture. You do your best and be as honest as possible with knowing what the limitations are. Also we probably needed more of a budget LOL practically speaking we proposed and did something that was very unaffordable and also not very sustainable. This is something upon reflection now I think a lot about with our installation work. The lack of sustainability for these temporary ideas. I think we could have challenged ourselves more to make this aspect a lot better. In terms of navigating problems like that of potentially missing information – making an exhibition with a strong engagement component allows people to tell you what is wrong with the info or in other cases tell you more information on something you presented. I think it’s something we try to do with our work today quite a bit, which is to make room for people to tell us what we missed and why we might have missed it.

Performance artist Sara French playing Reena Smith a Community Outreach Officer for 7 Continents in Markham, Ontario.

What did you learn about creating more choices around acquiring a place to live and what type of housing is available, as well as how those choices can manifest in Markham, Ontario?

SR ⤳ For myself, the project wasn’t propositional. No one visiting our intervention into the Strickler House at Markham Museum encountered an active statement about how Markham, or any other municipality in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, could/should/might re-orient to achieve more inclusive and more equitable housing.

The project included ‘case studies’ from every continent. And while each case study was diligently researched—each one including these incredible 100-year scans of each nation’s housing policy. However, they ultimately stood as characters, or as rhetorical foils, simply providing a mirror to how narrow the Canadian housing cultural imaginary simply is.

A phrase Chis, Aliya, Natasha, and I returned to during this process was a ‘house is not a home’. Reyner Banham and Francois Dallegret famously created a project called “a home is not a house”. Reversing the position of those two concepts “house”, and “home”, presents a way of thinking about the difference between dwelling in a home and acquiring wealth through the financial vehicle of the house. For me this raises the question: what forms housing imaginaries?

As I interact with folks who develop portfolios of rental properties, I am struck by how their relationship to housing mirrors attitudes and practices first rehearsed in Home and Garden TV series from the early 2000s. In speaking with them I sometimes feel like I am witnessing a re-run. The immense number of houses flipping shows from that period, communicated one singular message, that is: a house is not a home, but a financial vehicle.

A home’s “value” derives from its occupancy and use—the home is an infrastructure for the nurturing and reproduction of life. A house’s “value” derives from its exchange value. People raised on HGTV live in houses, not homes. As they make choices about how to change them, renovate them, redecorate them, through the central concern of how those changes will add value to a future sale.

For Banham and Dallegret, the architecture of the home dissolved through the introduction of media systems, radios, televisions, etc. Dallegret’s iconic drawings literally represent it as a bubble! Through the representation of housing as a commodity in popular media the home dissolves, from a place into something merely exchangeable—notably producing a bubble of a different magnitude.

Performance artist Sara French playing Reena Smith a Community Outreach Officer, engaging visitors at the Buying & Selling pavilion in Edmonton

Through the interaction of visitors, how did you find that people made decisions around housing? Was it as you expected?

CP ⤳ After talking with Sara (who was responsible for most of the front facing engagement). The stories about people getting upset at her because they were not sure whether 7 Continents was a real or fake organization is still classic to me. I was happy we all did a great job making it seem like this org was completely real and creating some weird form of legitimacy. I think watching people talk about the floor plans and seeing certain housing types have dedicated communal spaces or seeing denser type housing from other parts of the world and what it could mean for them was very interesting. We were not telling people that any of these things were bad or good. We just said here they are, what do you think. This I feel was a small dig and contrast to the planning process in Ontario, which often gives residents limited choices in either/or settings. The whole thing about Buying & Selling was about making people think a bit of their needs and wants when choosing housing and ultimately revealing that they probably never had a choice in the first place.

“The ‘choices’ we showed were to present alternate ways of living – to show the people of Markham what is possible, and in fact that there ARE alternatives, that we don’t have to have few options.”

When you say that you proposed “new choices in housing based on global profiles and housing typologies” to visitors, what do you mean?

NB ⤳ Markham’s housing typology is quite typical of North American suburban development. Developers create a style of home, slightly modifying its layout and external appearance, but ultimately replicate the design for the entire community. I think we have come to expect this type of design, which is not good or bad – it just is. The “choices” we showed were to present alternate ways of living – to show the people of Markham what is possible, and in fact that there ARE alternatives, that we don’t have to have few options. Of course the diversity of choice globally is due to local conditions and culture, but it doesn’t mean we can’t implement these here either. We can iterate, we can choose differently.

SR ⤳ Rather than housing typologies, I think perhaps lifestyles is a better word. A building typology is an architectural concept while I think the lifestyles that we presented were much more synthetic. They moved beyond architecture to incorporate issues of tenureship, financing, construction processes, political governance, among other issues. Not every case study addressed each of these topics, but each of these topics were addressed across the 12 case studies. A housing typology can be deployed in different contexts to create very different effects. In that sense, representing housing systems requires a broader view.

Also, it was a work of invisible theatre. Sara French, through her performance of Rena Smith, held open a space of self-reflection for visitors. If they choose to, they could examine their own assumptions and beliefs about housing in relation to our marketing copy describing different housing systems. In this sense, viewers’ beliefs and values about housing were the site of intervention. A second live version of the piece was presented in Edmonton. Based on Sara’s anecdotes from both Markham and Edmonton it seems like the visitors experienced moments of self-insight relating to unexamined assumptions about housing.

From what we know, the heritage house location of the exhibit was something given to you for the project— did it come to have any significance for it? Did it end up contributing any meaning?

NB ⤳ It definitely created a stronger connection between our material and where the visitor was digesting the material. It felt more of an embodied experience.

CP ⤳ I don’t want to pretend we treated it as something…It became a place to showcase the work and rules to be followed…Also just as a side note the museum is like a kind of retirement home for heritage buildings. So it’s like they take these significant homes or buildings, remove them out of their context (mainly because of new development) and place them all together so it can become this faux town. PS this is another project…

“The market has become a series of unhealthy quick decisions that put people in situations where they cannot not even consider basic considerations. The housing market we have is not for people, it is for balance sheets.”

Considering that the affordability crisis has continued to worsen through the years in the GTA and many cities across the globe— were there some lessons learned from the project that you think would help us better navigate the crisis today?

CP ⤳ Very simply, I think today the market has become so weaponized that the idea that you even have time to choose or think about where you would want to live and if that would be right for you or your family (if you have one) is not even possible. The market has become a series of unhealthy quick decisions that put people in situations where they cannot not even consider basic considerations. The housing market we have is not for people, it is for balance sheets.

SR ⤳ What is the reach of an artwork? 1960s counterculture artists, like the Merry Pranksters among others, made the claim “change your mind to change society”. I would say change banking practices, or housing policy, and change society—these levers establish the limits of choice.

Jack Layton’s book “Homelessness: How to End a National Crisis”, first published in 2000, describes one moment when housing policy was changed and then details the policy choices effect. In the early 1990s Brian Mulroney ended Canada’s National Housing Policy. Layton’s book, focused on homelessness, registers how one fallout from Mulroney’s choice was the introduction of three previously unseen demographics into Canada’s homeless population—families, women, and children.

In 2018, The Globe and Mail reported that forty percent of Toronto’s shelter beds were refugee claimants. In this brief reflection, exploring all the connections between these two moments isn’t possible. However, one simple conclusion we might draw from these two events, separated by thirty-years, is how Canadian housing policy continues to leave vulnerable people exposed to immense hardship.

Responding to your prompt for more actionable insight… both Sweden and India have dedicated financial institutions that lend to collective forms of building like multi-unit cooperatives. In both countries these institutions are over 100-years old. Austria provides federal dollars directly to cities to build affordable housing units each year. I recall Vienna buildings regularly and in significant quantities… thousands per year. The city has experience building, and for that reason, they even experiment! Singapore was a British colony. During colonization, it had significant slums. The British did attempt to ‘renew’ them but failed. Upon gaining independence Singapore established a housing agency. As I recall, the agency’s responsibilities encompassed all aspects of a housing system (commissioning, finance, procurement, design, construction, settlement, maintenance). Where the British failed, this agency succeeded, and flourished. Each of these vignettes, which we studied in the making of Buying & Selling, present other housing systems and imaginaries that are worth considering in relation to Canada.

Prior to March’s lockdown I was doing a series of interviews with folks on the West Coast regarding a housing development called Emmaus Place. It is ~80 units of affordable seniors housing (100% below market rate) in Langley, a suburb of Vancouver. Sheppard of the Valley Lutheran Church, and Community Catalyst Development, partnered on the project and are co-owners. Without checking my notes, SVLC put forward land and capital, while CCD, a not-for-profit developer, brought development experience. CCD has worked with several other Lutheran churches to introduce housing onto their sites in inventive ways, although their portfolio is much broader.

Through these interviews I was trying to expand my own imagination related to what/why/how housing can be built. I was interested in mapping the large and small partnerships that enabled this project to be conceived, and enacted. The degree of mutual support, between skilled members of SVLC’s congregation, CCD, Langley Planning and the Mayor’s office, Van-City Credit Union, and others, is so important to recognize. At the start of the project Van-City Credit Union gave SVLC a forgivable loan enabling it to undertake a feasibility study—this is just one small example of what infrastructure for building affordable housing looks like.

To address the GTA’s perpetual housing crisis, thinking about housing as a system that encompasses commissioning, finance, design, materials procurement, construction, settlement, and long-term maintenance, is so important. What the above example demonstrates is that ‘unlocking’ affordable development, requires partnerships that can align around a wider set of goals than a pro forma can describe. In the context of the GTA, there are numerous examples of religious institutions redeveloping their properties. In contrast to the approach SVLC took, which led to affordable seniors housing, these religious institutions cash out. X.x

What does your utopic version of a housing system look like? How does it work?

NB ⤳ Housing that has a greater integration and appreciation of nature and the elements.

CP ⤳ Housing is treated as a right not as a commodity. Let’s start from there…

Do you think this is something that we can work towards in actuality? Where would you start?

NB ⤳ Yes and no. No because the GTA is already densely populated so to try to reintegrate back with nature feels impossible. That being said, smart development, the cultivation of new ecosystems and carbon positive/passive house development can steer us away from old methods.

“I live in a co-op built in the mid-1980s. […] It is an example of how housing can function as more than a financial instrument and reflect ambitious ideas about design, equity, and access.”

Looking back on the process, what lessons did you take away from this project? Did it impact your own buying/selling decisions in your personal life? How?

SR ⤳ Buying & Selling invited comparison between different housing systems. Each housing system presented different qualities, none were perfect, although there was always something that one could find desirable.

Like the Galapagos for Darwin’s canaries, each housing system creates a set of conditions that foster certain ways of living over others. In the context of Canada, the detached neighbourhood is still a prominent model of development and it is very much oriented towards the dream of buying. A 2019 Globe and Mail story identified the most indebted places in Canada. Detached neighbourhoods, built over the last fifteen years, have the highest debt to income ratios. Households in these areas spend the most each month on servicing their substantial debts—they are exposed to the risk of insolvency.

It’s meaningful to question the idea of the individual and individual choice. The housing studies researcher, Richard Ronald, has demonstrated that in countries with minimal support for elderly people national policy re-enforces homeownership—building equity for old age. Do the folks described above, living on the brink of bankruptcy, choose what they aspire to? Isn’t it the nature of systems to structure what is and is not possible? That might be a difficult proposition for an artist to take given how much energy is exerted both cultivating a sense of individuality as well as then performing that “difference”.

I live in a co-op built in the mid-1980s. Like every ambitious housing project in Canada the enabling conditions were created by CMHC. One of the founding values of the co-op was to provide accessible units to folks with physical disabilities—this remains a priority and is reflected in the current membership. Ontario’s accessibility act came into effect in 2005. This building embodied those principles twenty-years early.

It is an example of how housing can function as more than a financial instrument and reflect ambitious ideas about design, equity, and access.

If there was more work that you could build on with this project, what would you like to do? Is there anyone you’d like to work with?

SR ⤳ From May 2019 to May 2020, I worked with a team of folks at the Daniels Faculty of Architecture on an exhibition called “Toronto Housing Works”.

It looks at the neighbourhood unit structure, repeated across the GTA, as a site for architectural intervention—adding housing, along with rethinking transportation, landscape, and social infrastructure. Like many things, it’s been side-lined by the pandemic.

It challenges Toronto’s zoning practices which protects detached neighbourhoods from any kind of change what-so-ever forcing Toronto’s residential development into towers.

CP ⤳ I think the project we are about to start with CERA is exactly the project that will be a fantastic continuation. The reason I say this was that Buying & Selling was meant to give people a space to think about the market, their role in it, and how the choices they can or can make it and inform it. Our work with CERA is about working with people to understand how to change what we have and create something that goes beyond the classic ideas of private property and housing as a commodity to a place where housing is a right and about people.

Some final thoughts from our Creative Director, Chris:

CP ⤳ In [my] view, Toronto needs more sustainable housing. Is our city ready to handle a population influx, particularly the kind that’s brought on by a crisis of some kind? I’m not sure urban designers are up for that kind of demanding thinking. Those are the kind of topics we’re really interested in, and what we want to keep exploring.