Retrospective of a Crisis

💭 Project Description

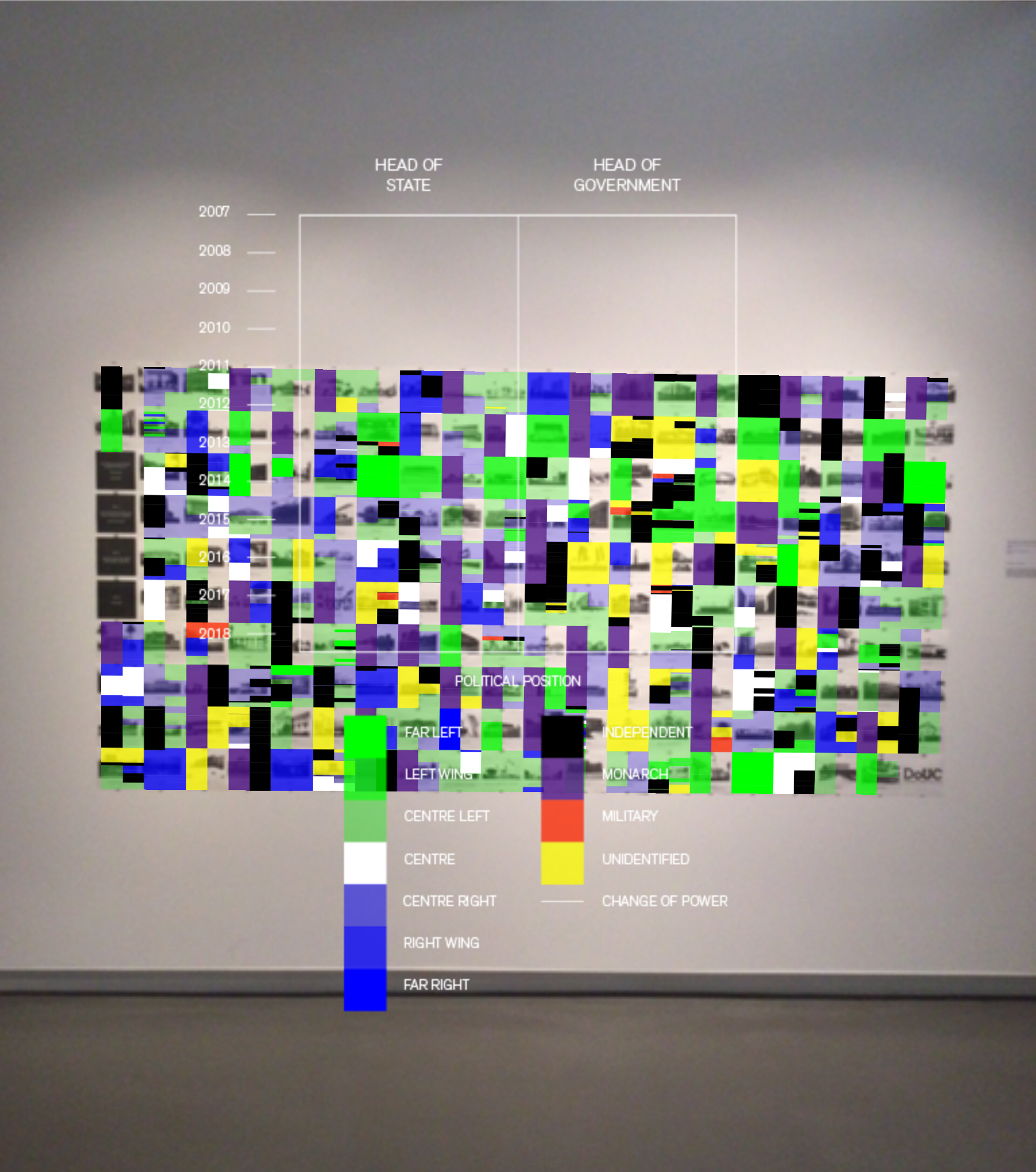

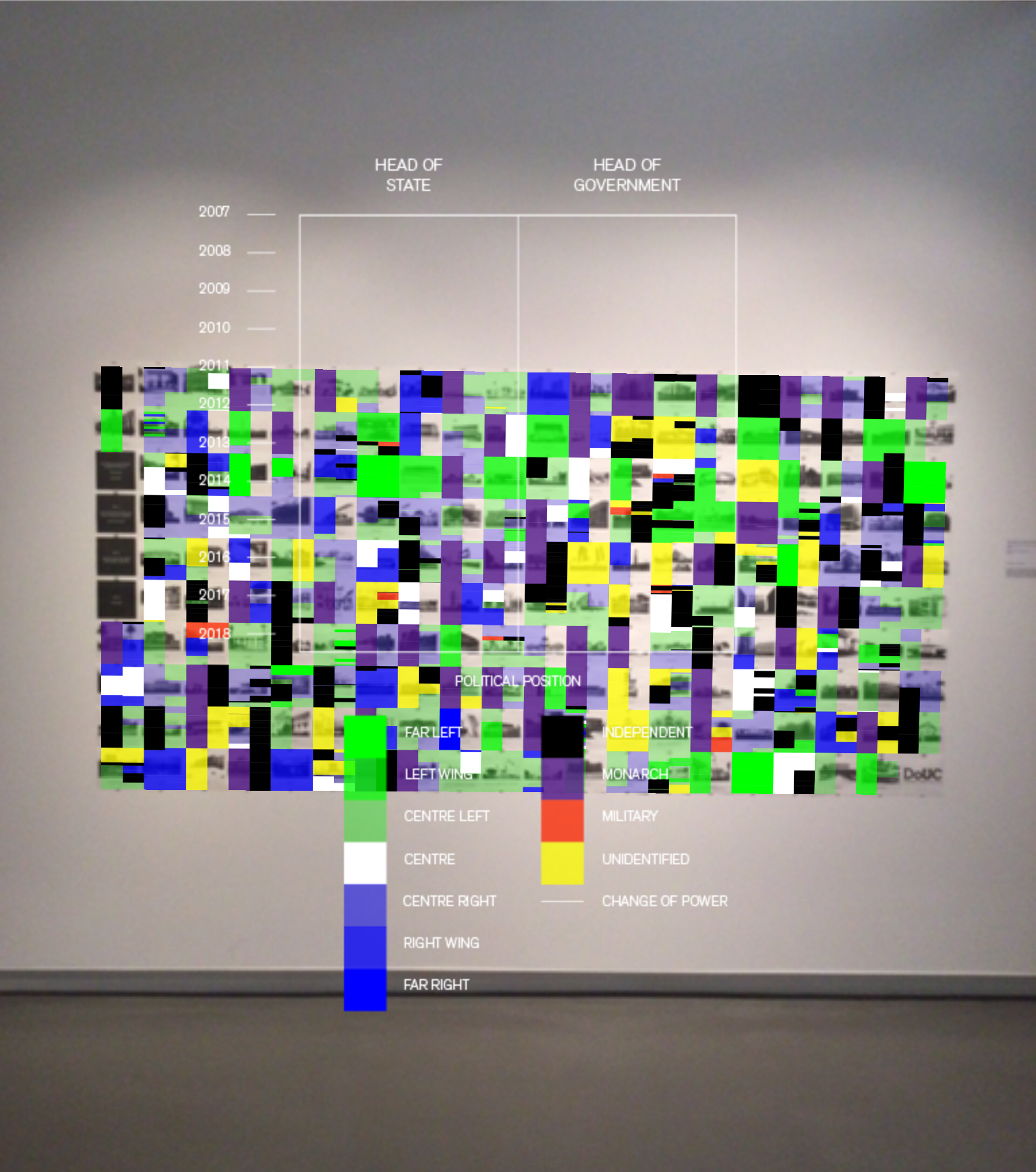

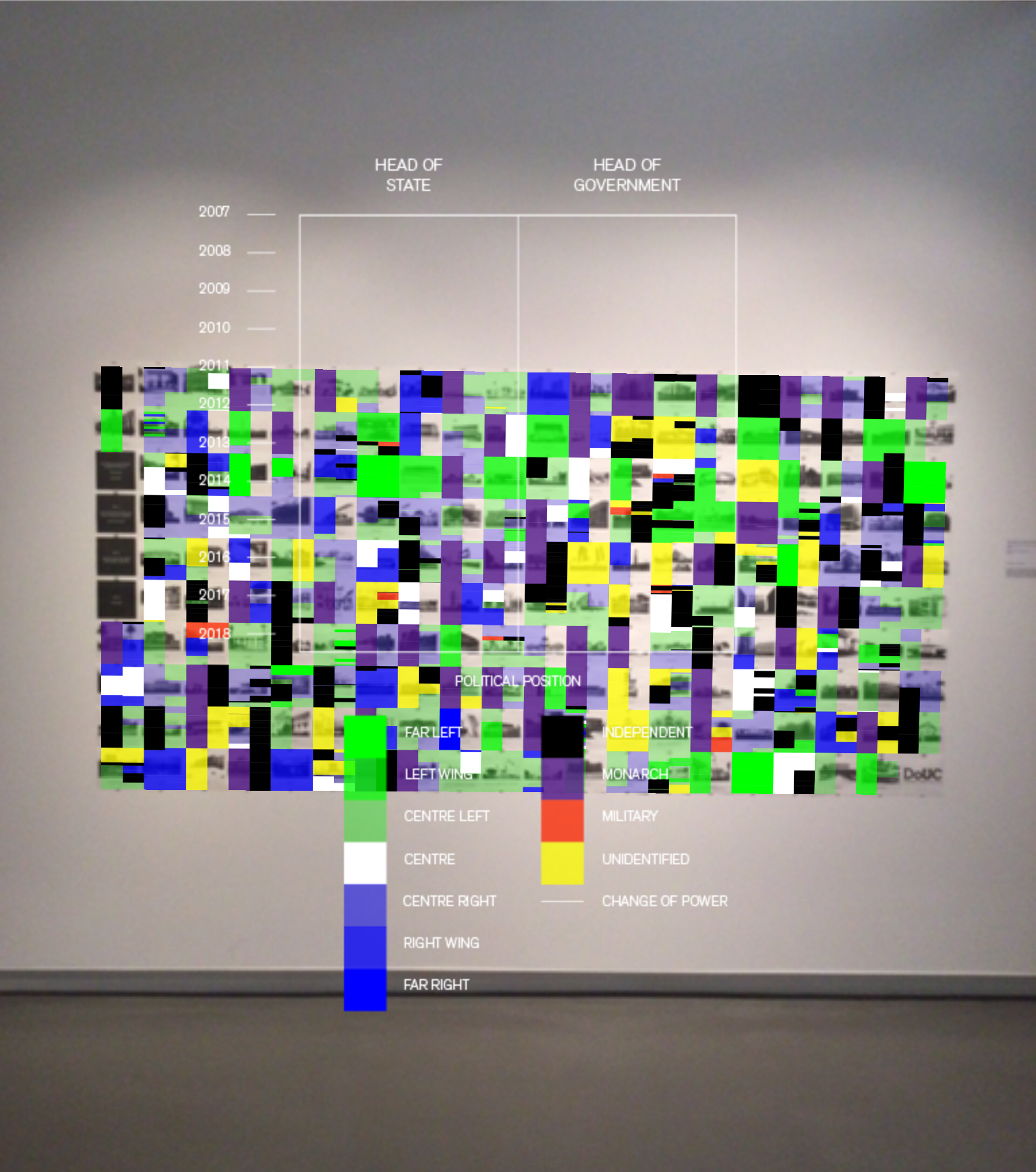

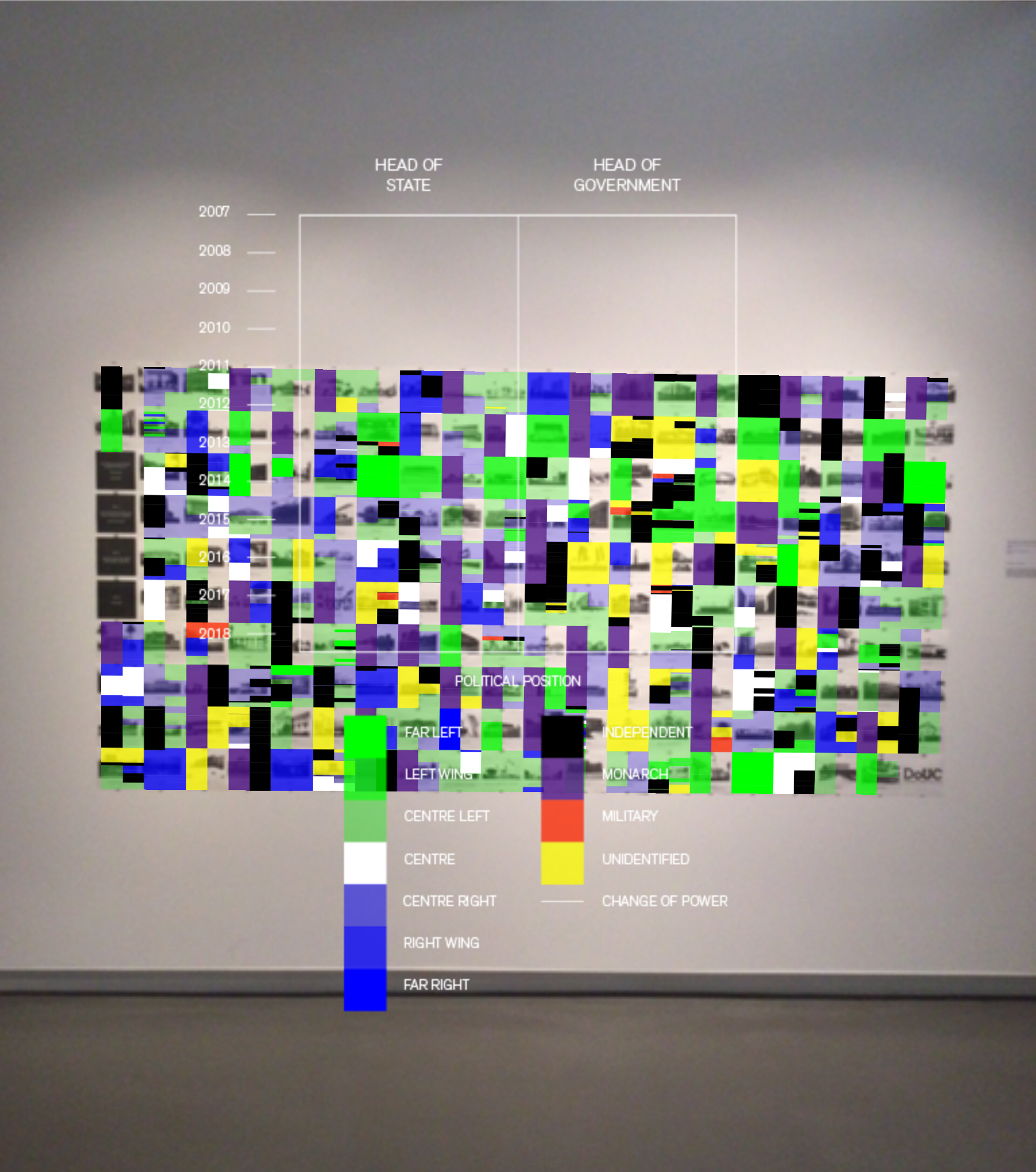

Ten years after the detonation of the sub-prime mortgage market and subsequent domino effect of collapsing global financial market, DoUC initiated an exploration into perceived and documented outcomes—as experience in forms which are not necessarily financial—since the peak of the crisis in 2008.

We must ask ourselves; how have we moved on? Could we possibly have moved past something that hasn’t really left us?

We can begin this process with a retrospective of perspective—a post-occupancy of the Crisis. Department of Unusual Certainties will mark the 10th anniversary of the Crisis with an exploration into perceived and documented outcomes, as experienced in forms which are not necessarily financial, since the peak of the Crisis in 2008. The goal is to create a series of stories and visualizations that draw comparison with no implication of necessary correlation, and illustrate what it means for one figurative century to die so another can live.

We understand that the Crisis is a milestone that will one day be regarded as ushering in the present and therefore worth reflecting on. Retrospective for a Crisis does not attempt to provide answers, only to pose a series of questions through which to create better understanding of the past decade and its impact on our present moment.

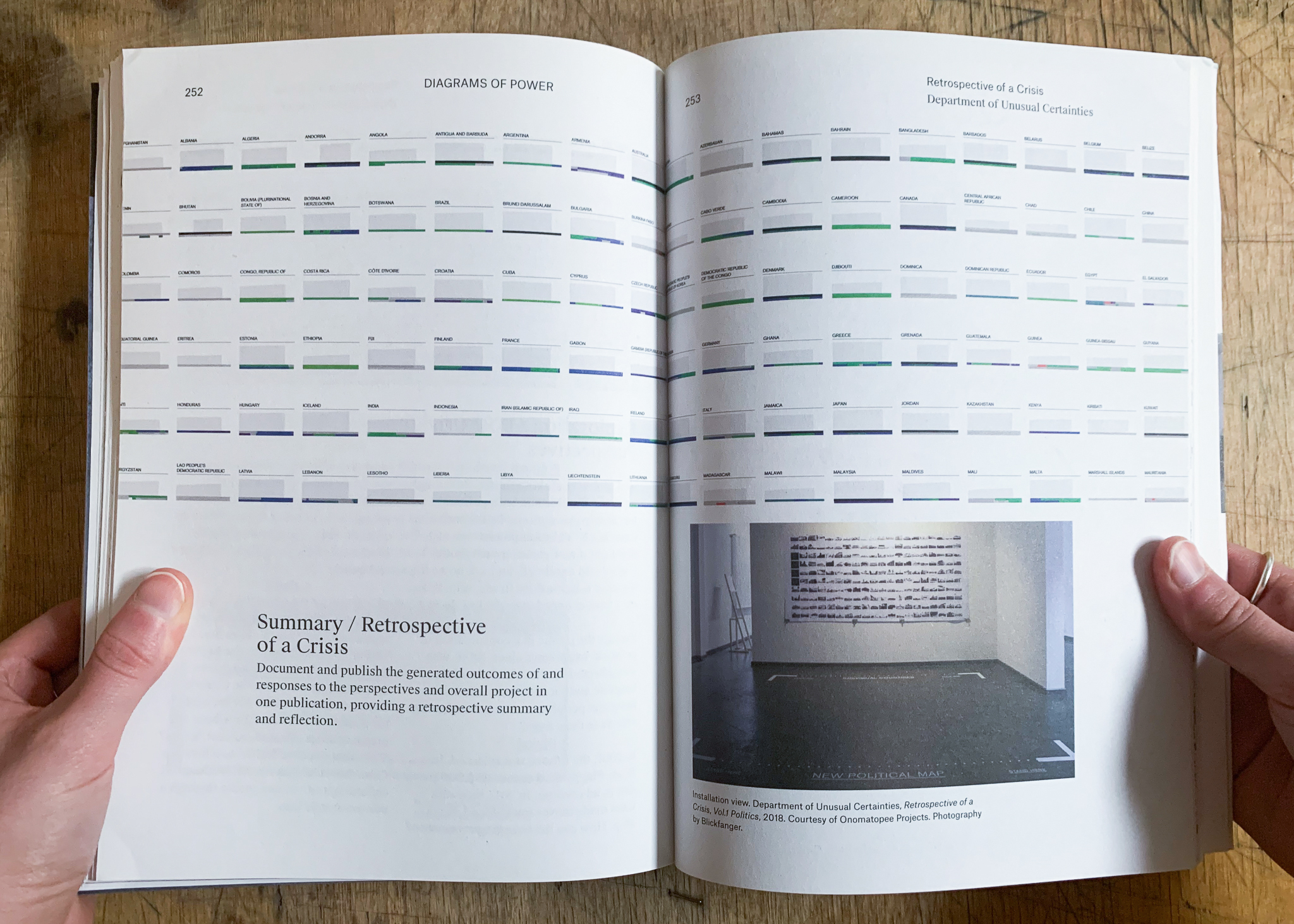

Retrospective of a Crisis was first showcased at Diagrams of Power in July 2018.

The project team included: Christopher Pandolfi and Sam McGarva.

Retrospective of a Crisis feature in the Diagrams of Power publication by Patricio Davila

RoaC exhibited in the Diagrams of Power show at the Onomatopee gallery in Eindhoven, Netherlands in 2019

To help launch our new, DoUC.fun webspace, and to commemorate DoUC’s 10 year anniversary, we have organized an interview series highlighting past DoUC projects.

We wanted to take this milestone opportunity to revisit projects in a fun and reflective way, calling on the perspectives of both past and present DoUC team members. Shifting from objective and brief project descriptions, we revisited our work with a renewed intimacy. With more personality. We hope this series provides deeper insight and understanding to past projects. Or, is simply a fun read!

To help you navigate this series, we recommend first reading the project summary for context. Then, you can explore the interview dialogue. Enjoy! 🙃

ℹ️ The Retrospective of a Crisis interview was conducted with Chris Pandolfi (CP) and Sam McGarva (SM).

In your own understanding, what was this project attempting to address?

CP ⤳ When this project originally started, what it was trying to address was this is this thing… so you have to go back in time for this— the studio started in 2010 and that’s two years after the financial crisis and one of the things that was always very interesting was this idea of the economy or of how the economy is a determinant factor of how people have their feelings and their lives and and all of these things. So the things that were always noticeable about this crisis were that there was, first of all, no repercussions— there were no repercussions for power. Things just went on as normal. But, as we kept making more projects, as we kept talking to more people, we kept understanding that this crisis was becoming more and more relevant.

It was not relevant in the way of things like job numbers or loss of money, but it was determinant of this whole feeling. At that time was what everybody is feeling today, especially if you’re young— about job prospects, property, and all of these things. That general feeling was starting to take shape more and more. There was always the uncertainty of being young and knowing what your future is, but what was becoming more and more clear was this idea of the uncertainty, of it being very certain that things were not going to happen for you because of the ramifications of this thing, the crisis. Even more to that, there was this other idea that people kept calling it a “financial crisis”, when in the past we had used this word “depression.” So we’re in a depression, the numbers stated that we were in this depression, but it was a crisis. The idea is that a crisis can be overcome. So when DoUC was innovators in residence of the Design Exchange, we were actually going to make an exhibition called “Terms of the Crisis,” where we were going to document the crisis up until that point. That exhibition got cancelled, the DX all of a sudden decided they didn’t want to do an exhibition like that. We were going to do this very highly infographic, highly curated thing about people’s feelings about the crisis with numbers and all of these things. We had this whole thing— we designed the whole exhibition in the sense of how we want it laid out. What’s funny is that if you look through some of the publications of the DX, where you could see things like Play Nation and these kinds of things, there’s also the Terms of the Crisis name within the catalogue. And also, “Saturn Eating His Son” by Goya was actually the exhibition poster. So, all these things happened.

Then time went by, we made a lot of other projects, and then all of a sudden 2018 came about. We started talking about this in late 2017, because technically the crisis started in 2007. It was the beginning, this is when you started to see the Lehmen brothers and all of these things, but the crash doesn’t come until a little bit later. So we thought it would be great to do a “10 years later” approach. How do we do this, retrospective of a crisis, how do we showcase the fact that for 10 years this thing that supposedly happened 10 years ago is actually still existing. We wanted to show that and so we talked about making a technological timeline, because what was also interesting about when we started looking at the ten years is that if you look at the launch of the iPhone and if you look at where computing power was, it was online when the financial crisis happened. So, in the end we had this great burst of technology and innovation and people’s lives being changed, but at the same time there was also this crisis that was happening. The other idea was to do a series of interviews with people around just how they’ve been feeling over the last 10 years. The one that we ended up sticking with was the political one, which is essentially the Retrospective of a Crisis Vol. 1.

We started by asking ourselves: how do we show politics through this. Because we didn’t want to just show the numbers of the crisis, we wanted to show what changes had occurred. What if we took every single country in the world and actually looked at how their political leadership has changed, and more importantly, how their political parties and ideology has been shaped through these ten years. Essentially what we started to understand immediately was this thing that we always knew, which was that at the end of the day power maintains power, and they know how to act. If you actually look through all of those pieces of information that we collected and visualized, you’ll notice one thing: there is a small shift at the beginning of the crisis where there’s a change, but after that things generally stay the same. They stay the same because there is no mass political system. Their control and power looks different in different places, but at the end of the day power is maintained. A conclusion of all that work shows you one thing— nothing changed. Even after a massive event like an economic depression nothing changes in the sense that wages don’t go up, new types of political systems aren’t created. If you look at the Great Depression, what happened especially in North America in the United States and a lot of other countries pre WW2 was that you basically had the birth of a social welfare state. You had a massive shift in the way that people thought about Capitalism, how they thought about service delivery, how they thought about other things— we didn’t get that. What we got was not necessarily a change, what we got was a hyper movement towards the thing that already brought us there. So for me I guess what the project showed for everybody or what it was trying to address was that nothing changed, and, if anything, it got worse.

SM ⤳ This project originally had five elements:

- Economic History of the Crisis – create a baseline for the rest of the project through an understanding of how and why the crisis occurred

- Political History Post-Crisis – understanding shifts in political leadership and effects on health and wellbeing

- Personal History Post-Crisis – the human experience of life going on during and after the crisis, emerging from engagements with communities across the GTA

- Digital History Post-Crisis – discovering directions for the future of technology products, systems, and services by examining the past

- Cultural History Post-Crisis – analyzing representations of the crisis in pop culture to create a point of reflection on both the crisis and the project itself

While this project was originally meant to be a kind of time capsule, it was also structured to showcase the studio’s interests and values by exploring new technology, engaging with people, and building out a story for the audience to interpret through their own experiences.

Unfortunately, at the time we only had the capacity to deliver on the political history—which is a conversation for another day about the somewhat arbitrary line drawn between art projects and design or research projects, and how each are funded (or not).

Initial drafts of the political spectrum diagrams.

In the two years since its initial release, let’s attempt to address the original questions posed by the project: How have we moved on from this crisis? Could we possibly move past something that has not left us?

SM ⤳ I always liked to imagine the first question as ambiguous. Are we asking in what ways have we moved on, or how have we brought ourselves to move on? The project attempts to answer the first, and the audience is left to consider the second.

CP ⤳ When you think about moving on, you always have to ask who’s moved on. So for some people, and this is where the adage “never let a good crisis go to waste” comes in, what you saw that happened was an amalgamation of not just power, but you also saw an amalgamation of capital. Which essentially led us to one of the greatest times where inequality became stronger— and we’ve been living with this allowance for the system to maintain itself.

So, people had to change and people change, and because people are amazing things, they know how to figure themselves out. But for other people, they didn’t need to change. Instead they became stronger. And, I think for me that was another thing where these people are like, “oh are we still living with the crisis?” Well, now we’ve got Covid so people are going to focus on this, but you have to keep in mind that the Financial Crisis exacerbates anything else that comes after it. We never did the thing that we needed to do to alleviate the injustices that the crisis caused, so we’re still living with its consequences. These consequences have now gotten us to our current point— that’s how crises work. It’s not the thing that gets you, it’s all the things you didn’t do before that get you. Covid is a great example of that because, okay, why do we need everybody to make sure that they that they sell isolated that they do these things? Because our systems can’t maintain everybody getting sick. Even though the virus might not kill you, the healthcare system will. The fact that you can’t work or eat will. The fact that you’ll be homeless will. You don’t kill people with a virus, you kill people with the systems that can’t sustain or protect you from a virus. So, all our systems at this point, which were already weakened by the neoliberalism that started in the 80s and continued in the 90s that weakened all our social systems, are basically dying a death by a thousand cuts. It’s just a slow bleed out. So we’re in another phase of a bleed out, and so, yes in a sense we can’t really possibly move past something that hasn’t really left us yet— we’re getting more cuts day by day.

That second question seemed to imply some difficulty in attempting to move on from something that has not yet left us — seeing as we’re entering into a new global recession, this time precipitated by a pandemic, was there something you found during your research in the project or your time since then that would help us better navigate an ongoing economic crisis? How can we avoid some of the mistakes made during the period explored in the project?

CP ⤳ So the thing is that this project was never meant to map action; we weren’t saying that this is what you can do to get out of the crisis. What this project was, as part of a long lineage of other projects, was: look at this, explore this, think about this. The problem may be that people want to create actions after the crisis, but what nobody got time to do, was reflect on the idea of why this thing exists in the first place. So, this is not one of our projects where action is the outcome, it’s slowly allowing people to just reflect.

We created a database of information for people that we allow them to see—and it’s very difficult for people to understand why somebody would do that, but for me it’s always understanding the fact that people don’t have the time to delve into some topics. Personally, I don’t know about these things because I’m smarter than anybody else. That’s not why I know these things, that’s not why I can connect things, or say this is this. It’s because I have the time to do it. My career as a designer, the way that I teach, I’ve created space for myself to make sure that I know about these things and then I’ve attached them to my economic means. So it’s easy for a guy like me to say these things. It’s like talking to a plumber and asking them “how does shit go down a pipe,” and they’re going to be able to tell you super clearly how that happens and in super amount of detail, but they’re not going to be able to tell you about the financial crisis. For us these kinds of projects are just meant to be for everyone—and we’re not even reaching that audience, we’re really just reaching the people who are going to come to an art show or go to a large scale exhibition and even they don’t know about all of this. In the end, the actions that you create are not ones that you are in charge of. You allow people to think about and reflect on what they’re seeing and decide what actions they’re going to take.

This is a really big thing— in systems like what we’ve mapped or what we visualized with Retrospective of a Crisis, and these political relationships of countries, and the timing and all of these things, is that people want actions at the scale of the system in which you’re visualizing. The other point is that’s not necessarily how you tackle those problems. You have to allow people to understand their system, the system that they’re living in. The context and the gaps that they see to allow them to know what change they need. It’s an idea of diffusion as opposed to a large-scale approach.

And, that’s always been really interesting to us to explore— this idea of diffusion. It changes what you’re doing— when you’re doing something separately, you may never connect to each other, but this allows the system to change because you’re going against the status-quo. It is also transparent about the fact that we’re not experts at everything. You know your life and how to approach it better, so here’s the information. Instead of always telling people what to do, I like that approach.

“Some of the hardest working people that I know, their ambitions are to put a roof over their head, raise their kids, have a hobby, and live a life. Live a life, and on the weekends they can see and eat with people they love, they can go outside for a walk, they can watch their child become safer than them— all of this is an ambition, and the problem is that these ambitions get lost.”

What does a world that has truly “moved past” a crisis of this magnitude look like to you? With consideration to the original crisis explored in the project, the financial crisis of 2008.

CP ⤳ The thing here is that there’s a bias in my hands right, and you know this is not like some big vision for the world— ambition looks very different to other people. I think that what the crisis exacerbated was this idea that people at the top are ambitious and this is what you get when you work hard. Now that’s bullshit. Some of the hardest working people that I know, their ambitions are to put a roof over their head, raise their kids, have a hobby, and live a life. Live a life, and on the weekends they can see and eat with people they love, they can go outside for a walk, they can watch their child become safer than them— all of this is an ambition, and the problem is that these ambitions get lost. There’s this idea that this is not enough and you should want more, but for a lot of people this is enough. The pursuit of happiness looks a lot different. So for me the saddest part is the amount of people on this planet that just can’t sit down at a table and have a safe meal with people they love is the change that I wanted to see. I wanted to see that mother, that father, that sister, the brother, the friends getting together and feeling safe around a table where they could just laugh and talk, and not be worried about not just the uncertainty of everyone’s life, because everyone’s life is full of uncertainty, but the uncertainty of of an economy that you have no grasp over.

This was an opportunity for us to reshape the way that we can connect with the way that we work and the way that we live and the way that we treat people. We build society in an image of safety and equity. The fact that systematic racism is an open conversation right now is one of the greatest things that happened during this crisis. It finally shows that this system is part of the other systems of the other crisis. Systematic racism played a role in the financial crisis. They’re all embedded with each other and then what that crisis did was open the window and showed us all of the things. And we chose not to take any of them or to do anything about it. Because if you can make people feel the most basic kinds of safety and security and everything else comes on top, then it’s going to become ambitious in a different way. Because you’re not going to be worried that your ambition is going to cause you to be on the street. That’s the problem, that’s what that latency is like. It’s the latency of a whole generation of people being stunted.

You should be able to live a good life without owning any property and you should be able to live in housing and get things that are just as great as everybody else.

Do you think that world is realistically attainable for us? In our lifetime?

CP ⤳ Very much so. It’s not that hard.

It’s very difficult right now because people are waking up and they distrust government systems. With validity by the way, they’re valid to distrust them, because in a country like Canada you have corporate welfare— like, oh, we’re gonna not let you get so bad, but you know we’re gonna give big payouts to this guy and this guy will allow us to have all this. It’s a very Western approach. It’s corruption but it’s corruption without being corrupt.

Then at the same time what you had happened, and especially during the time of the crisis, was that you had people move their trust and move their faith into digital technology. Social media is allowing me to do this, I can make money from it. It was a very weird thing where now all of a sudden all this trust went towards another kind of, let’s call it hegemony, and it pushed power to a new type of power. What we saw in the 2016 American election was a new relationship between two hegemonies. If it wasn’t for the way that we use the data— and now how many people are waking up, like oh shit, for 10 years 12 years we’ve been giving everything to these companies. They’ve been growing large because of us. The difference is when you want something back from a government, and you live in a democracy, you can get it. How the fuck do you get to Mark Zuckerberg? How do you get to Jeff Bezos? These are private companies. We gave our needs and wants, and our trusts for wanting to change society, we gave it to the wrong people. They create distractions for us, distractions from what our existence is, in some cases.

So, in achieving these kinds of things what’s going to be important again is to make people realize what’s actually important to themselves. What their ambitions are. The life they want to live, the life they want their children to live, the life of their neighbours, what do they want out of that life. It’s going to take a little bit of time to get everybody to understand what that is, and then to show what that could look like. That’s work. That’s the work now! This is not the pivotal moment of other pivotal moments, it’s another moment where we have a choice. We have to save the planet or we have the choice to destroy the planet.

And we keep choosing the thing that never helps us! Which is capitalism. It’s the most abusive relationship— humans created their own abusive relationship and they just don’t want to get out of it. If you look at all of us as a group, it doesn’t do anything for us!

The thing about capitalism and power—and I don’t want to use them interchangeably—you don’t care about power unless it’s effects happen to you. That’s the problem; unless it’s happening to you, you’re not aware of it, and that’s been power’s greatest strength. It’s silent. Real power is silent.

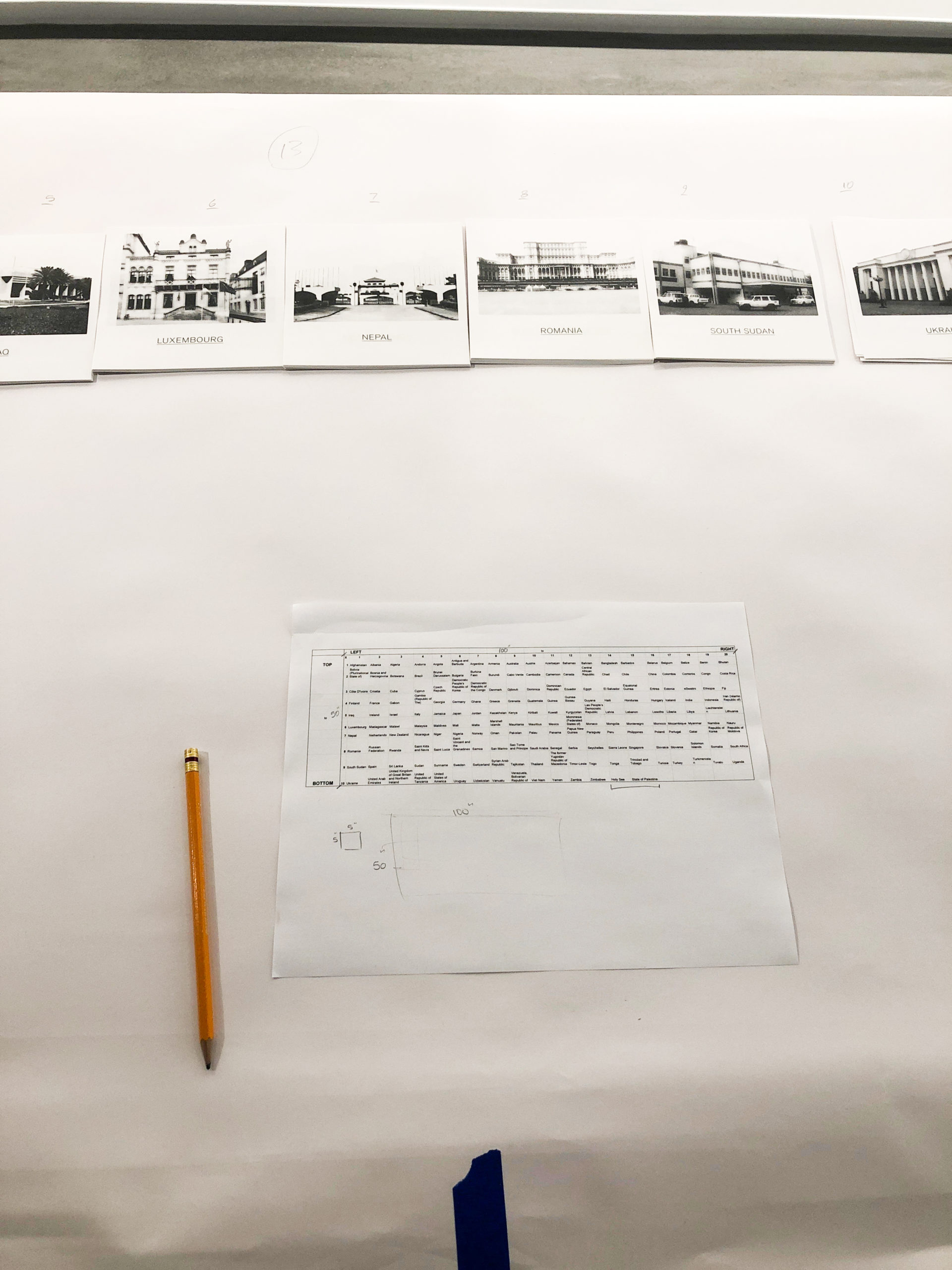

Chris & Sam designing + testing the final layout of the parliament buildings.

What are your primary thoughts when looking back on the project? How do you think it might still be relevant today?

CP ⤳ The one thing now that it should do is create a lot of questions. At the end of the day we used questions to build a project that hopefully made people ask more questions. And now if you’re asking questions about the project, you’re asking questions about the content. What has changed in those places? What happened? Two years is a long time. What is similar about this crisis to the crisis going on now? What are the patterns that we see? I always hope that the legacy of that project is not something where people are like, “oh that was a really great project,” I hope they understand that it’s possible for systems to be explored.

This is what I want everybody to know— the second that someone tells you that something is complex is the moment when you need to start exploring it, because nine times out of ten that shit is not complicated. The word “complicated” is a scare tactic, it’s used to scare people away. We create complex systems because we have something to hide. When you really look at those systems, they’re not complicated at all. Their fundamental qualities are doing something very simple, which is just getting people who have power, more power. Retrospective of a Crisis was a project that looked complicated, but was visualized in a very simple way and had a very simple message: power maintains itself no matter what. That’s it.

If people look at that project from now until the end and just say, what did I learn? What’s still relevant? Power maintains itself. I hope that one day someone’s like, that project is not relevant anymore. Because if it’s not relevant, it means we, as humans, did something to change power structures.

With this reflection in mind, is there anything you would want to explore more of or have explored differently within the project?

CP ⤳ I want to finish all of them— I want to do them all. I wish my whole two years of my life, since the time we conceived this project to the time we first presented the first one, I wish that all I could do was spend time on this project. Ultimately, I only got to do one of them. It’s a huge regret that we didn’t finish it.

Final setup for “Diagrams of Power” at the Onsite Gallery in July 2018

“A whole new story began to emerge, of colonialism, decay, terrorism, and international investment.”

What were some challenges you faced during your exploration? How did you navigate them? How did they shape the final outcome?

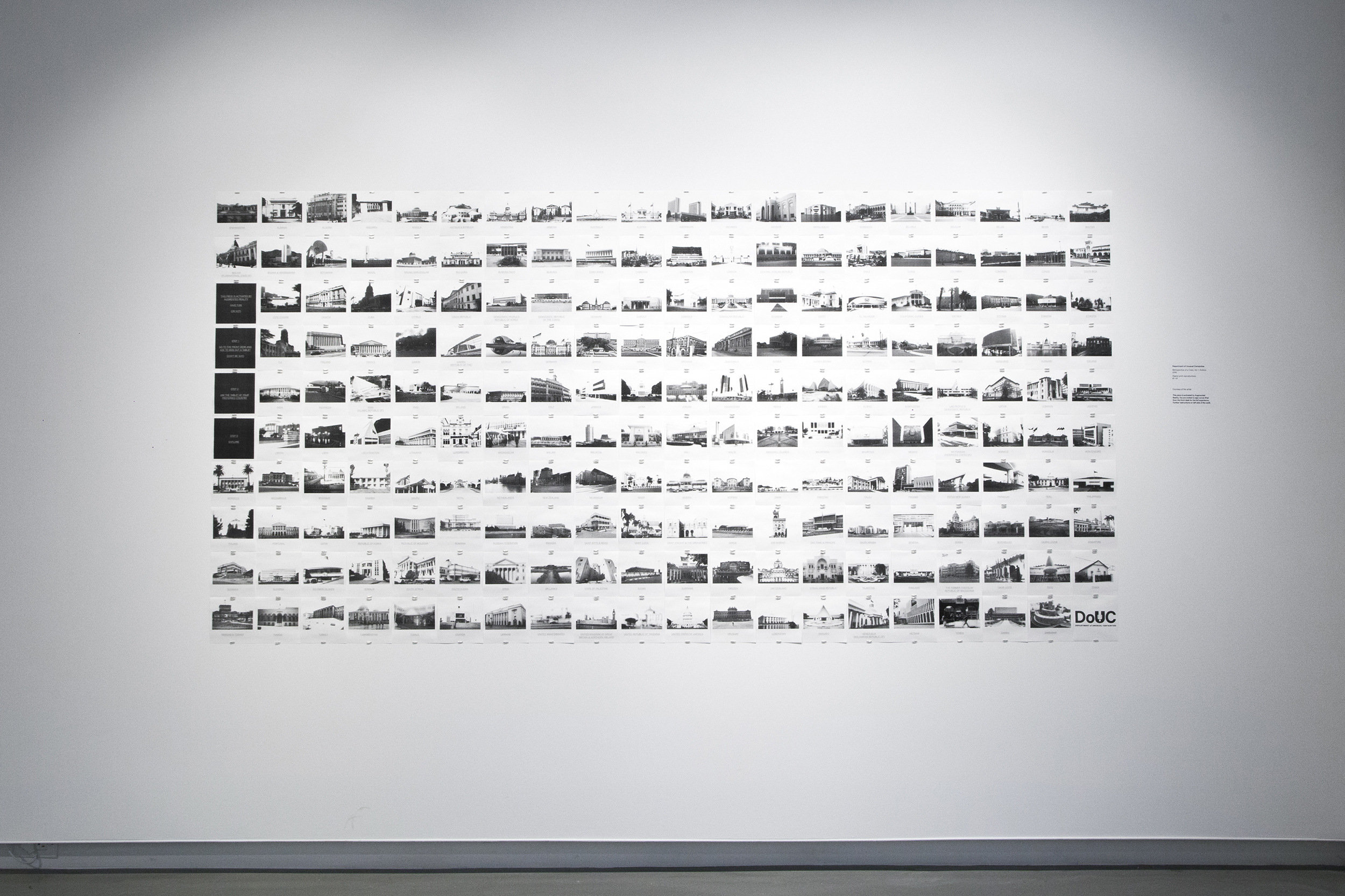

SM ⤳ At one point we were collecting faces of political leaders to collage, and we calculated out the time it would take to collect, process, and cut out all these little faces and it was going to be DAYS. So we chose to use national legislative buildings instead. A whole new story began to emerge, of colonialism, decay, terrorism, and international investment.

CP ⤳ Just doing the research was just barbaric. We had a main source that we used from this one government group, then we had the UN source, and then in some cases we had to go to Wikipedia because we needed the political party better defined because it wasn’t defined somewhere else. Then this political party is being defined as center left, but then you read about them and you’re like this party’s center right or right wing. So, going back and forth and just double checking that this stuff was correct was a lot. For example, when Donald Trump got elected, we put into the spreadsheet that he was right-wing, because the Republicans are a right-wing party. The reality is, Donald Trump’s not part of the right-wing party, he’s actually a far-right fascist, but they don’t call themselves far-right fascists. So we didn’t, we couldn’t take those liberties. I can’t take the liberties with the things that I really know about, because I don’t really know about that other thing and then I’ve got no consistency in my methodology. So, we have to go with how they self-reference. We have to double check it and make sure if the political party’s web page says that. That’s what you’ve got to say, even though that’s what they say but that might not be what they do.

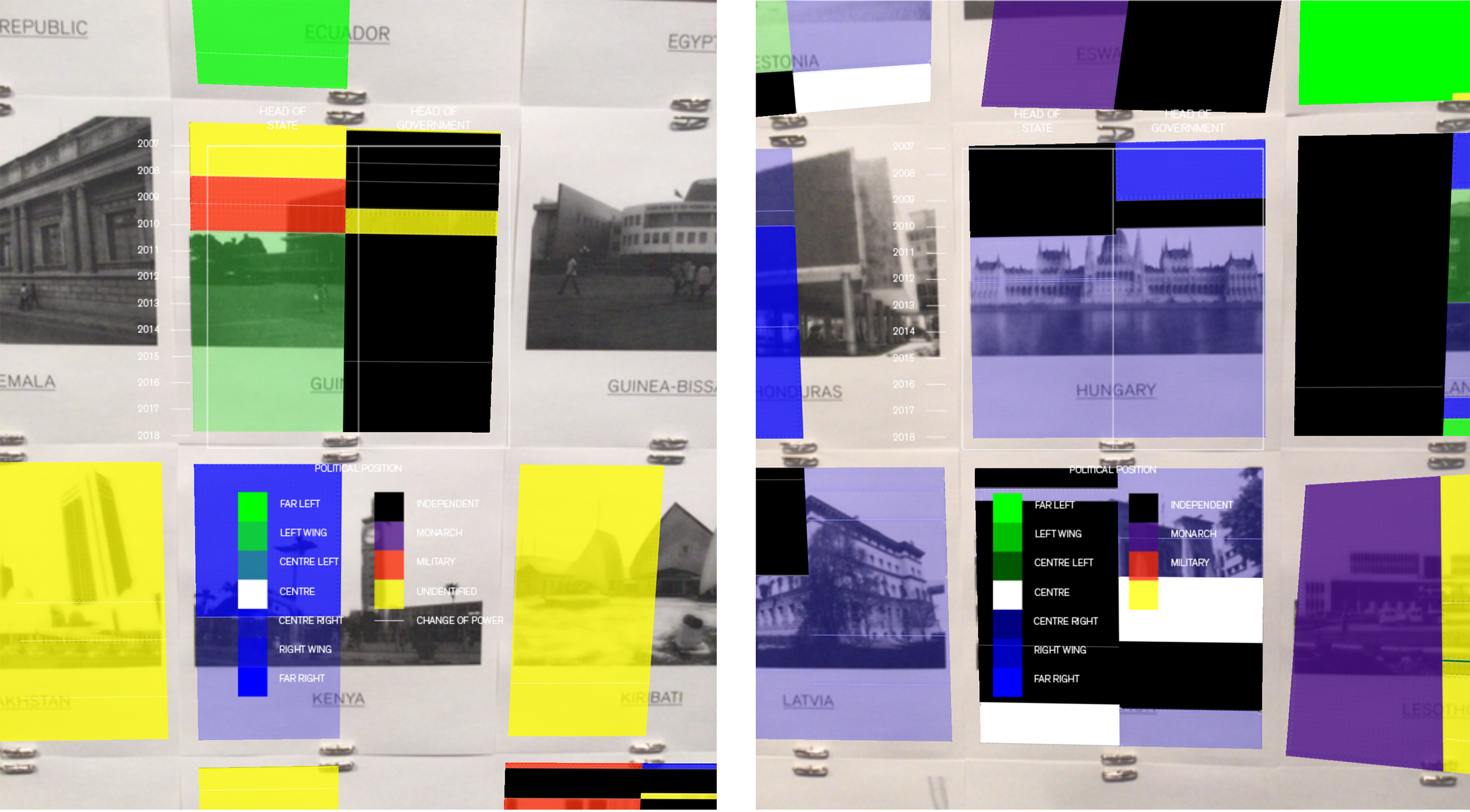

AR data-vis map overlays

What was something interesting that you learned during the process that you still remember to this day? Why did it impact you so?

CP ⤳ I think the thing that we saw that was really interesting was the amount of parliament buildings in different African countries that were being financed by China. The Chinese government was building new parliamentary buildings in Africa. So there was that fact, and the other fact is when we showed all the political buildings— the reason we showed it is that, and this wasn’t part of the project essentially, but we always do something like this where we make a visual representation of saying something highly political without saying it. Without it being the main interaction, but, what did we learn? If you look at all the political buildings in most of the world you learn one thing: if you didn’t believe that colonialism has left its impact in the globe then you are completely blind. We are joined through this architecture. We wanted to illustrate how architecture is a banal thing, it never responds to actual issues, because at the end of the day it was the visual representation of global colonialism. Why the fuck does this building look like this in this part of the world? This has nothing to do with this culture and yet this building looks like this. It’s because this system and this structure has been built by this colonial power. Why does it all look the same? Ask yourself that.

We were originally going to do all of the heads of state, I was gonna research every single head ever and Sam almost killed me. I was like, yo man we gotta get on these heads, like we gotta start prepping heads, and she’s like, Chris we’re never going to finish this project. Then we talked about the meaning of it we were like, okay, this is not actually what’s important. What’s important is this idea of symbolism.

Me and Sam cut each one of those buildings out and gave it the texture— we created the diffused glow and everything. And I think that might be the point, there needs to be a rigor, there needs to be a lot of repetition in this kind of work. The reason is because when you’re hypnotized by the repetition of the actual work to make the project, it actually brings out these other kinds of more abstract thoughts. When you’re because you’re giving labor to this project, you’re like like I’m spending six fucking hours photoshopping fucking buildings, what else am I thinking about? I’m thinking about why this project’s so important. It’s reminding me about it.

Setting up for “Diagrams of Power” at the Onsite Gallery

How has the project impacted your understanding of the world?

CP ⤳ You want to believe that the things you think aren’t true— a lot of the reasons why I like to make these projects so I can try to prove myself wrong. I don’t want to believe that there is a series of power structures that govern us, but yet every time I make these things that’s all I find out. I’m looking for this not to exist and every time I get it I make another one of these kinds of things, all I find out is that it exists even more than I thought.

What was so telling about it was that the crisis sacrificed all these people for show. There’s always these little ones, the ones that go right away. The elections that were right after changes things, but then that guy that went, that guy comes back. This is what it is. You fucked up, you go do your time, you come back.

Is this something you hoped your audience would also reflect upon? What else?

CP: I never think about that. I never think about the thing that I want people to think about with these projects. That’s up to them and that’s very personal. I think that’s where I’ve been able to free myself— I think very early on I was really worried about what people thought and then I became more concerned with the idea of, are we making an experience for people that will allow them to get to a place that I don’t care about. Which is what they think. Like in the sense of, I don’t want them to think something specific. That was a big criticism we got, like why don’t you just tell people how to think. But that’s the problem! That’s why we’re making the project! We don’t want to tell people how to think, we want them to actually think.

Why is that only some people should be interested in thinking? What kind of elite bullshit is that? That not everybody on this Earth just wants to sit outside look at a tree and just fucking think. Who said that’s only for some people. That only some people can have thoughts or original ideas. That’s fucking bullshit!

For me it’s really nice to create things for people that are like, wow I thought about that and I never did before. Good! As you should. Because you have your right to think. That’s a big fucking thing. We don’t outlaw it, we don’t say in Canada you know you don’t have the right to think, but we’ve done everything in our power to make sure that people actually don’t have time. The fact that thinking has become a privilege is crazy. How many times have you said to yourself, “I haven’t had time to think about this.” How the fuck is that possible?! What else are you doing that you can’t use your brain!

Experiencing the AR at the “Diagrams of Power” exhibit on July 12, 2018.

Augmented Reality (AR) as the medium for presenting the project was an interesting choice, what motivated you to employ it? What kinds of audience interactions and reactions were you hoping to inspire through it?

CP ⤳ I think there were two ends in this. One, there was this personal push— I was tired of making timelines in a graphic way. I just felt like I reached my peak and I didn’t want to do them anymore. I started just getting this reputation, like oh yeah there’s Chris, he makes timelines. Chris makes visual content, okay, and I make them really well. I also make them really well because I learned from the best person who makes them. I learned from the guy who taught me how to make them, this was the guy who made all the best timelines. So it’s like of course I’m going to make good shit, because I know how to make it, I got taught to make it that way. So for me I felt that we were getting a little stagnant and we weren’t really thinking about showing information in different ways. The other thing was if we’re going to make this project, we should learn some new skills, we should try something else out. So those were the impetus for us in the studio to try something different with the timeline.

On a small side note, was the use of AR and consequent interaction a metaphor for anything greater within the project?— Whether it was intentionally designed to be as such or accidentally relevant.

CP ⤳ The reason why I got so interested in augmented reality early on was, and I always try to push it all the time, was because I like this idea of being able to build a space where its impact can disappear. The other thing too that I wasn’t seeing was a lot of data vis with AR. That’s what drove it— could we take our data vis work to the next level. So, I think it was the experimentation of augmented reality. And when we decided to go with the augmented reality what we really started to think about was about the multiple experiences people are having. When you approach the project you’re confronted with all of these buildings and you’re like, okay why are we talking about a crisis? What crisis are we talking about? Then you would put the iPad and explore more to find that it’s about political power— the idea of visualizing what was inside those buildings. What did it look like inside? It was this x-ray of the building and then this visualization. We really thought about why we were doing this. We want to experiment with this, but if we’re going to do it then we need to do it the best way that we know how, between the abilities and skills of our experimentation. Once we started to understand what the AR was capable of we knew that we could make a story with it. So we designed that story. In the end, okay it’s in AR, but who gives a fuck. In the story we really need AR in order to make that story the way that we wanted to. We didn’t let the tech inform how we wanted to do something, we understood what we wanted to do with the tech and then made a story that could bring and involve the technology.

There was something about seeing that RGB colour palette on a black and white photo, and then a map that gets created at the end— a new political map. We were presenting a new map of the world and that was the power move, the big idea. When people see that it says so many different things.

SM ⤳ To me, the medium was a metaphor. The legislative buildings and their architectural styles as more permanent symbols of power printed and displayed for all to see at all times, and the individual leadership—power that is constantly in flux—displayed through augmented reality, visible only to those who have the right tools in the right place.

Sam testing out the AR map at the DoUC studio in July 2018.

Do you still think that AR was the best choice for presenting the project? If so, is there anything more you would have wanted to do with it to further push the experience for the audience? If not, how else would you have presented it, and why?

SM ⤳ I was disappointed that the iPad required for the experience needed to be stored at the front desk and signed out to use. If we created this experience today, I would definitely use WebAR so almost anyone with a smartphone could access it relatively seamlessly.

CP ⤳ I don’t know— it’s a good question because I never think about it.

You know when you see the look on people’s faces— after a certain moment you make so many things and you try to remember like that thing and you remember that the choices that you made were not just arbitrary choices. You spend time on it. To think about if I would’ve done it differently? I don’t know, because everything led me to that.

To end this interview, reflect on how your personal intersecting identities influenced this project. How did these aspects of your identity influence the project (in all phases of exploration and creation)?

CP ⤳ You have to really work hard not to try to be biased. You have to do your best because at the end of the day— I think this is a really good question, because I’m also learning when I need to not be that person who is doing that anymore. But, a lot of these projects there is no separation between them, they are my identity, they are who I am. One of the biggest challenges I have is to let go of that. In the sense that I will always drive the project to be it.

What was interesting was, when we were making some of this stuff, and we started this, I was talking to Sam. She was like a teenager and then as she started learning about this stuff in her life, I was learning new things. Instead of learning the facts, I was learning the perception of the facts. That’s what helps me shape my ideas. I’m a lead on a project like this because i’ve made it my life to be fucking nosy about this shit. But, when I see other people who work on this stuff for the first time and how their opinion is getting stronger, or how they’re changing the way that they think about things, or the way they’re like, oh that’s interesting, and the way they take this thing and then turn it into that thing— that’s what I learned from this project. The problem is that I’m so entrenched in my politics now that I don’t listen to people. It’s very hard to convince me of power structures. It’s really hard to give me information, to tell me, Chris this doesn’t exist. I don’t believe that. So when you’ve gotten to a point where you’ve put your feet into the sand about this thing, it’s very hard to take yourself out of that.

But also, I don’t want to not believe that because then fundamentally what do I believe in. What am I working towards?

When we do client work, obviously it’s very different for me, but when we do this kind of project everything is dumped into it. Like everything, I’m mentally drained, emotionally exhausted, and physically exhausted. It’s everything when I get to the show. It’s that last bit of energy trying to share with people. Then afterwards I’m a mess for two days usually. It’s done, I don’t want to look at it again, I don’t want to think about it again, I got this out of me, and I don’t have to worry about it. It was just as introspective as it was retrospective.

They’re not projects to me. They’re expressions.